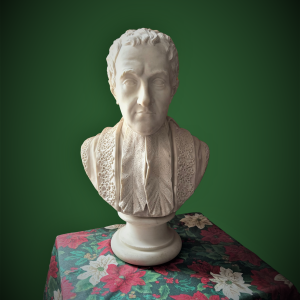

Michael Rysbrack, Marble bust of a young boy or putto

Mid-eighteenth century marble bust of a young boy or putto by Michael

Rysbrack (1694-1770)

White bust of a young boy, circa 1725, by Michael Rysbrack (Antwerp, 1694-1770,

London), c. 1725, marble, 26.2. cm high excluding the socle, 39 cm high overall; 19.5 cm

wide (shoulder to shoulder). c. 1725.

Price on POA

Description

Literature:

A Catalogue of the Genuine and Curious Collection of Mr. Michael Rysbrack, of

Vere-Street, near Oxford Chapel, Statuary,…which will be sold by Auction, by Mr

Langford and Son, at their house in the Great Piazza, Covent Garden, on Saturday the

20 of this Instant April 1765, lot 32.

M. I. Webb, Michael Rysbrack Sculptor, London, 1954, p. 186, and n. 5 on p. 186.

Katharine Eustace, ‘The key is Locke: Hogarth, Rysbrack and the Foundling

Hospital’, The British Art Journal, Vol. 7, No. 2 (Autumn 2006), pp. 34-49.

Comparative Literature:

Bevis Hillier, in Chapter 2, ‘The End of the Baroque’, The Social History of the

Decorative Arts, Pottery and Porcelain, 1700- 1914, (London: Weidenfeld and

Nicolson, 1968), pp 46-65.

Katharine Eustace (ed.), Michael Rysbrack, Sculptor, 1694-1770 , City of Bristol

Museums and Art Galleries, 1982 (exh cat).

N. Penny, Catalogue of European Sculpture in the Ashmolean Museum, 1540 to the

Present Day, Oxford, 1992, Vol. III, no. 457, pp. 17-19.

Katharine Eustace, ‘Robert Adam, Charles-Louis Clérisseau, Michael Rysbrack and

the Hopetoun Chimneypiece’, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 139, No. 1136 (Nov.,

1997), pp. 743-752.

Zorka Hodgson ,’Chelsea Boy’s Head after Francois Duquesnoy – Il Fiammingo’, ECC

Transactions, Vol 15, Part 2 (1994), pp. 184-9.

Hilary Young, English porcelain, 1745-95: its makers, design, marketing and

consumption, London, 1999.

Malcolm Baker, Figured in Marble: the Making and Viewing of Eighteenth Century

Sculpture, London, 2000.

Andrea Bacchi, Catherine Hess and Jennifer Montagu, eds., Bernini and the Birth of

Baroque Portrait Sculpture, Los Angeles and Ottawa, 2008 (exh. cat).

G. J. V Mallet, ‘Some Baroque sources of English ornamental porcelains’, a paper

read at the weekend seminar ‘Fire and Form – The Baroque and its influence on

English Ceramics, c. 1660-1760’, 26th-27th March 2011, published by the English

Ceramics Circle, 2013, pp. 123-146

The recently discovered marble bust of a young boy (Fig. 1), with its English

provenance, is undoubtedly that listed under the heading ‘Busts in Marble’ as, lot 32,

the bust ‘of a little Boy, after Fiamingo’, in the catalogue of the sale of Michael

Rysbrack’s works (during the sculptor’s lifetime, and on his retirement) by the

auctioneer Langford in Covent Garden on 20 April 1765.1 The marble bust bears

neither the inscribed name of any sculptor nor a date, but nothing turns on that, as on

stylistic grounds alone, it is undoubtedly the work of Rysbrack; and in any event

Rysbrack only infrequently signed portrait busts of his own invention, so he is

unlikely to have signed a bust produced by him in marble where the model was not

his own creation but that of his predecessor sculptor and compatriot, François

Duquesnoy, (‘Il Fiamingo’ or ‘Il Fiammingo’) (‘The Fleming’) (Brussels,1597– 1643,Livorno).

Even in his lifetime, as evidenced by the catalogues of sale of his work,

Rysbrack acknowledged his debt to Duquesnoy by ensuring that his illustrious

predecessor was credited with the invention of works Rysbrack carved after

Duquesnoy’s models. Indeed, he recognised the additional value accruing to his own

works from their close association with the work of Il Fiamingo.

Born in Antwerp in 1694, Rysbrack (who went to London about 1720 and died there

in 1770) is one of the most important sculptors to have practised his art in 18th-

century Europe, and was the leading sculptor in Britain between 1720 and the mid-

1740s, remaining one of the leading sculptors in Britain until his retirement in the mid-1760s.

A maker of funerary monuments, statues, portrait busts, marble fireplaces,

reliefs and architectural and decorative items and pieces of furniture, Rysbrack can be

credited with taking the first steps that led English sculpture out of the provincial

backwater in which it had languished for many centuries. In short, and of particular

relevance to his statues, funerary monuments and busts (which comprised by far the

part of his oeuvre), Rysbrack was one of the two finest portraitists (the other being the

French sculptor Louis François Roubiliac, 1702-62)2 in England between the death of

the painter Sir Godfrey Kneller (1723) and the arrival in London in 1753 of Joshua

Reynolds. Save for William Hogarth and Allan Ramsay (the latter of whom had

settled in London by about 1739), there were almost no first-class portrait painters in

England at the time that left a body of work of outstanding merit. This makes the

work of the marble portrait carver such as Rysbrack even more significant, and ‘when

compared with the painted portraits of the time the sculptured portraits will be found

to rank very high’.3 As Matthew Craske has remarked, ‘the monuments and busts of

Rysbrack and his competitors can justly be regarded as the forbears of the grand

portraits of the aristocracy that were the speciality of Reynolds and Gainsborough.’4

The prodigious production of portrait busts, statues and monuments by Rysbrack in

the two decades or so following his arrival in 1720, epitomises the extensive, if not

entirely novel, employment of classical precedent in the eighteenth century, and is

perhaps seen to best effect in Rysbrack’s celebrated busts of Lord George Hamilton,

1st Earl of Orkney (1733, Private Collection) and Daniel Finch, 2nd Earl of

Nottingham, c. 1723 (Victoria and Albert Museum, Mus. No. A.6-1999). The

influence of Rysbrack, a pupil of the Antwerp sculptor Vervoort – whose own Baroque

idiom was tinged with classicism – in the development of the classical tradition in

England was of the utmost importance and it has been remarked that ‘the main theme

which runs through nearly all his work and makes it a coherent whole is the classical

theme, the theme of heroes in Greek or Roman dress, classical draperies and more or

less static poses.’5

As regards Rysbrack’s marble bust of a boy and its link to Il Fiamingo, Jennifer

Montagu has written that,

‘It was for his putti that Dusuesnoy was most famous in his own day, and

ever afterward. The three tombs that he made on his own designs are adorned

exclusively with putti, that of Adrien Vryburch [or Vryburgh] in Santa Maria

dell’Anima [Rome] of 1628-9, that of Ferdinand van den Eynden [Santa Maria

dell’Anima] undated (Van den Eynden died in 1634) and all that remains of the

uncompleted tomb of Jacob de Hase in the Campo Santo Teutonico [after 1634]’.6

John Mallet has continued the narrative thus:

‘Bellori [Giovan Pietro Bellori (1613-96), Lives of the Modern Painters, Sculptors

and Architects, Rome, 1672 ] prints an adulatory letter written by Rubens to thank

Fiammingo for casts that the sculptor had sent him from Rome of the cherubs on the

Van Eynde monument, which shows one way in which Fiammingo’s work could

exercise its influence far afield. Jerome Duquesnoy of Antwerp, heir to the contents

of his brother’s Rome studio when the latter died prematurely in 1643, was in 1654

burned at the stake for homosexual proclivities, causing Fiammingo’s models to be

dispersed by sale in the South Netherlands, thus presumably hastening the spread of il

Fiammingo’s works through northern Europe.’ 7

It is well-known that putti from Il Fiamingo’s funerary monuments served as models

for painters and sculptors, and in 1968, while writing on Duquesnoy’s putti in Rome,

Rudolf Wittkower remarked that ‘the conception of the Bambino became a general

European property and consciously or unconsciously most later representations of

small children are indebted to him’.8 Even in the late eighteenth century Duquesnoy’s

children remained highly valued, and the then leading London sculptor Joseph

Nollekens RA (1737-1823), when enquiring of Panton Betew of Compton Street, the

silversmith and dealer in pictures and other works of art, ‘What do you want for that

model of a boy?’, received the curt reply from Betew, ‘Why, now, can’t you say

Fiammingo’s boy? You know it to be one of his, and you also know that no man ever

modelled boys better than he did. It is said that he was employed to model children

for Rubens to put into his pictures’.9 Mallet has noted that an unattributed funerary

wall-monument in Saint James’s, Piccadilly, London, by an as yet unidentified

sculptor

‘to a Frenchman who became the First Earl of Lifford and died in 1749 …bears

witness to Fiammingo’s enduring international popularity. The figures on the

monument are closely copied from Fiammingo’s second monument in Santa Maria

dell’Anima, to Ferdinand Van den Eynde, completed between 1633-1640. The Lifford

monument, though, adopts from the Vryburgh monument the idea of placing the

inscription on a fictive cloth.’10

Given Rysbrack’s origins in Antwerp and, as noted by Malcolm Baker, the sculptor’s

considerable output of ‘Duquesnoy-like heads’,11 which appear throughout his oeuvre

(other than portrait busts of unidentified individuals, although even there they appear

to have inspired one particular bust), it is unsurprising that he should have produced

(for specific patrons or even as a speculation, or possibly even for his own enjoyment)

marble versions of Il Fiamingo’s boys. Katharine Eustace has succinctly provided the

context:

Rysbrack was trained in a Northern European, specifically Flemish tradition, in which

infants secular and angelic had, throughout the seventeenth century, provided the

subject of ornament on monuments, in interior decoration and as objects of vertù in

marble, bronze, terracotta, ivory and stucco. His fellow countryman …François

Duquesnoy (1597-1643), Il Fiamingo, had established the genre, to the extent that his

name is synonymous with the type. Rysbrack’s master, Michael Van der Voort

(1667-1737), employed these small naked children on monuments such as that to

Ambroise de Precipiano (d1707, Malines Cathedral), and as a rustic Cupid to his

Venus (Royal Museum, Antwerp). A life-size crying boy in contemporary dress by

Putti appear in many of Rysbrack’s marble fireplaces, architectural works, and on

funerary monuments. These include the figures in relief on the fireplaces in the Court

Room of the Foundling Museum, London (1745-6), the fireplace made for the East

India Office, London (1729), and the fireplace in the Red Drawing Room at Hopetoun

House, West Lothian (1756-8) (the latter to the design of Robert Adam, Charles-Louis

Clérisseau); the two full-figure putti reclining upon the pediment over a door in the

Stone Hall at Houghton Hall Norfolk (1726-32), the two putti supporting an

architrave in the Victoria and Albert Museum (Museum No. A.4-1990, c. 1730), the

putti in relief on the decorative panel of the Allegory of Water with Putti Playing with

a Dolphin (National Galleries of Scotland, , acc. no. NG 2615, c. 1725-30); and the

putti in relief or angels in the round on the monuments to Sir Godfrey Kneller

(1723-30), Sir Isaac Newton (1727-31), and John Gay (1736) all in Westminster

Abbey, to Harriot Bouverie at Coleshill, Berkshire (1750-1), and to Admiral Jennings

at Barkway, Hertfordshire (after 1743).13

The marble bust by Rysbrack bears a close resemblance to the angel holding aside the

drapery that adorns the medallion high relief portrait of John Gay on his monument

by Rysbrack in Westminster Abbey, and to one of the angels on the monument to

Harriot Bouverie as well as to the boy on the viewers right side of the relief on the

fireplace in the Foundling Museum; and both the angels or putti on the monument to

Admiral Jennings clearly relate to the marble bust of the boy by Rysbrack in Fig. 1,

while the body types of those figures clearly correspond with the torso of Rysbrack’s

marble boy.

There are also many similarities between the marble bust in Fig. 1 and Rysbrack’s

marble portrait bust (Fig. 2) of Henry Frederick Harley, infant heir to the vast

combined London fortunes of his parents, the Earl and Countess of Oxford. Henry

died aged only four days in October 1725. His life-size bust, described by Eustace as

‘in memoriam, unique of its kind, may have been commissioned soon after the baby’s

death’ in 1725.14

The style of carving and surface finish of the marble bust of the boy (Fig. 1) are seen

on numerous busts by Rysbrack, and the specific shape of the torso and its truncation

(Fig. 3) as well as the truncation of the shoulders, with their concave curves, is

idiosyncratic of Rysbrack’s oeuvre, and can be seen on almost all of Rysbrack’s

portrait busts of males, including those recorded in the article and other such as

Alexander Pope, 1730 (National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 5854), John Barnard

1744 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Acc. No. 1976.330), and Francis

Smith of Warwick, c. 1741 (Private Collection).

In 1964, Margaret Whinney commented that ‘the form of’ Rysbrack’s bust of Daniel

Finch, 2nd Earl of Nottingham, c.1723 (Victoria and Albert Museum, Mus. No. A.

6-1999), which is also seen in the Orkney bust, ‘with its long concave curves below

the arms, is not derived from Antiquity, and may be an echo of the long form still

being used for busts in Rysbrack’s youth by his master, Vervoort.’15. Like those busts,

the back of the bust of the boy has the same distinctive and meticulously finished,

open, curved back. Rysbrack’s bust of Francis Smith of Warwick has the deeply

concave back associated with all Rysbrack’s marble busts, and a central support of

circular profile, obviously designed to be fixed to the circular socle on which it rests,

with an upper half-round moulding to the central circular support and a straight-sided

moulding at the base, almost identical with the back and support of the marble bust of

the boy in Figs. 1 and 3.16 The marble bust of the boy also rests on a socle of a type

unique in the eighteenth century to Rysbrack’s busts and which is, for example, seen

supporting his celebrated portrait bust of the 1st Earl of Orkney, 1733 (Fig. 4),17 and

on his historicising busts of Shakespeare (1760), Rubens (c. 1743), van Dyck (c.

1760), and Il Fiamingo (1743-6), amongst others.18