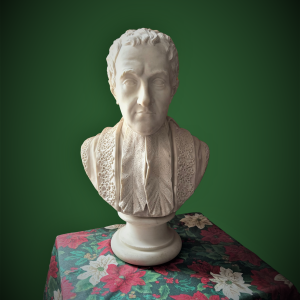

Nydia, “The Blind Flower Girl of Pompeii”

Nydia, ” The Blind Flower Girl of Pompeii”

By Randolph Rogers (American, Waterloo, New York 1825–1892 Rome)

Price on POA

Description

Created in 1853–54; this version probably carved in the late 1850s

Marble, approximately 137.16 cm (54 in.) high.

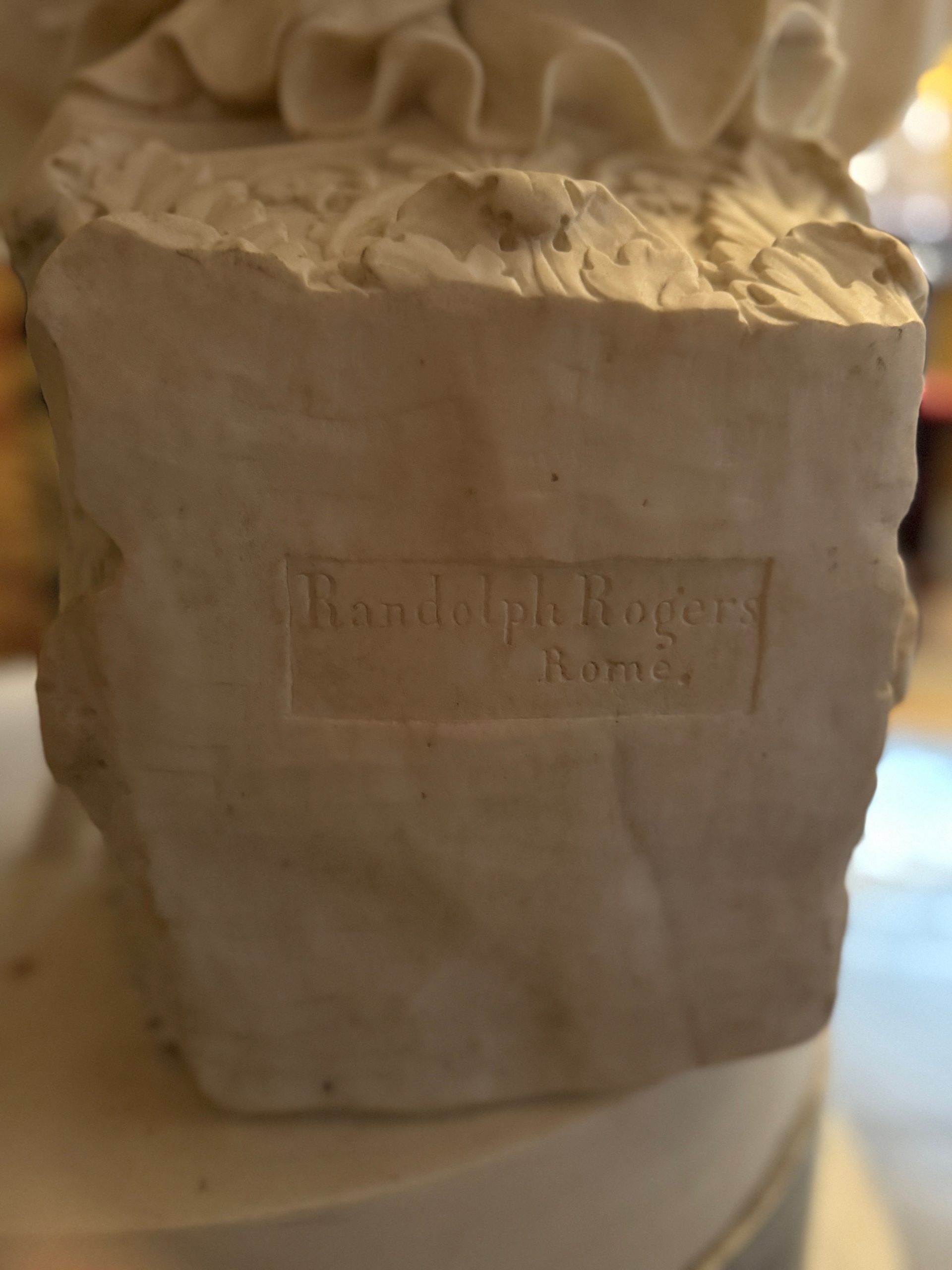

Signed: ‘Randolph Rogers Rome’ on the underside of the fallen Corinthian capital

Related literature:

Edward Bulwer-Lytton, The Last Days of Pompeii, Dodd, Mead and Co. (New York, NY, 1946).

Margaret Farrand Thorp, The Literary Sculptors, Duke University Press (Durham, NC, 1965), ill. p.

175, frontispiece.

Wayne Craven, Sculpture in America, Thomas Y. Crowell Company (New York, NY, 1968), p. 314.

Russell Lynes, The Art-Makers of Nineteenth-Century America, Atheneum (New York, NY, 1970), p.

147, ill. p. 148.

John K. Howat and John Wilmerding, 19th Century America: Paintings and Sculpture, exh. cat., The

Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, NY, 1970), p. 114.

Millard F. Rogers, Jr., Randolph Rogers: American Sculptor in Rome, University of Massachusetts,

Amherst (Amherst, MA, 1971).

Kenyon Castle Bolton, III, Peter G. Huenink, Earl A. Powell III, Harry Z. Rand, and Nanette C. Sexton,

American Art at Harvard, exh. cat., Fogg Art Museum (Cambridge, MA, 1972), cat. 68, ill.

H. Wade White, “Nineteenth Century American Sculpture at Harvard, a Glance at the Collection”,

Harvard Library Bulletin (Cambridge, MA, October 1970), vol. XVIII, no. 4, pp. 359-366.

The subject of Nydia, the Blind Flower Girl of Pompeii was drawn from “The Last Days of Pompeii”

(1834), a widely read novel by Lord Edward Bulwer-Lytton, which ends with the eruption of Mount

Vesuvius in a.d. 79. The novel was inspired by the painting The Last Day of Pompeii by the Russian

painter Karl Briullov, which Bulwer-Lytton had seen in Milan. Once a very widely read book and now

relatively neglected, it culminates in the cataclysmic destruction of the city of Pompeii by the

eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. The novel uses its characters to contrast the decadent culture

of 1st-century Rome with both older cultures and coming trends. The protagonist, Glaucus,

represents the Greeks who have been subordinated by Rome, and his nemesis Arbaces the still older

culture of Egypt. Olinthus is the chief representative of the nascent Christian religion, which is

presented favourably but not uncritically.

In a tensely dramatic scene inspired by the novel, Nydia, a blind flower seller, struggles forward to

escape the dark volcanic ash and debris of Mount Vesuvius as it erupts and buries the ancient city of

Pompeii. Her closed eyes and staff allude to her blindness, while the hand raised to her ear refers to

her acute sense of hearing. Clutching her staff and cupping hand to ear, she strains for sounds of

Glaucus (a nobleman with whom she has fallen desperately in love) and his fiancée Ione.

Accustomed to darkness, blind Nydia uses her acute hearing to find the two, leading them to safety

at the shore; but in the end, despairing of the impossibility of her love, she drowns herself.

The destruction of Pompeii is symbolized by the broken Corinthian capital beside her right foot; and

Nydia’s clinging garments, entangled in her staff, indicate her chaotic surroundings. In the second

half of the nineteenth century, the public was fascinated with such stories of Pompeii’s destruction

Because of its narrative quality, sentimental presentation, and classical features and proportions,

this sculpture was extremely popular with the American public upon its first being exhibited, and

became the most popular American sculpture of the nineteenth century. Rogers (who lived in Italy

and based this work on the classical Greek sculpture he studied in museums there) made a small

fortune on the more than seventy marble copies of Nydia that were commissioned by admirers and

carved by highly skilled Italian craftsmen in two sizes after the artist’s model. The present example is

of the larger size. Examples are in many museums in America and elsewhere, including The Art

Institute of Chicago, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art,

Washington DC, Princeton University Art Museum and the University of Michigan Museum of Art.

Praised for both his technical skill and sensitive interpretation of the subject, Rogers devised a

variety of surfaces for the life-size Nydia – the girl’s face, arms, and breast are smoothed with a

soulful translucence while the billowing skirt is cut into thin, dynamic folds. The movement of the

drapery, as it wraps Nydia’s staff and streams against her body to reveal her young figure, gave the

sculpture a dynamism and sensuality that resonated with Victorian viewers. The artist, based in

Rome, was probably influenced in the particulars of Nydia’s realization by the many Classical and

later sculptures on view in public and private collections there. Rogers said of her “the subject is so

beautiful, and the character of the blind flower girl so pure, that all who have a heart must feel

interested in her.”

*****

Randolph Rogers (July 6, 1825,Waterloo, New York – January 15, 1892,Rome, Italy) was an American

Neoclassical sculptor. An expatriate who lived most of his life in Italy, his works ranged from popular

subjects to major commissions, including the Columbus Doors at the U.S. Capitol and American Civil

War monuments.

Born in Waterloo, New York, he spent most of his childhood in Ann Arbor, Michigan. He developed

an interest in wood cuts and wood engraving, and moved to New York City about 1847, but was

unsuccessful in finding employment as an engraver. While working as a clerk in a dry-goods store, his

employers discovered his native talent as a sculptor and provided funds for him to travel to Italy. He

began study in Florence in 1848, where he studied briefly under Lorenzo Bartolini. He then opened a

studio in Rome in 1851. He resided in that city until his death in 1892.

He began his career carving statues of children and portrait busts of tourists. He was not happy

working with marble; consequently all his marble statues were copied in his studio by Italian artisans

under his supervision, from an original model produced by him in another material. This also

enabled him to profit from his popular works. His first large-scale work was Ruth Gleaning (1853),

based on a figure in the Old Testament. It proved extremely popular, and up to 20 marble replicas

5

were produced by his studio. His next large-scale work was Nydia, the Blind Flower Girl of Pompeii

(1853–54). It proved even more popular, and his studio produced at least 77 marble replicas

(“Randolph Rogers,” Susan James-Gadzinski & Mary Mullen Cunningham, American Sculpture in the

Museum of American Art of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA, 1997), pp. 58–61).

In 1855 he received his first major commission in the United States: great bronze doors for the East

Front of the United States Capitol. He chose to depict scenes from the life of Christopher Columbus.

The Columbus Doors were modelled in Rome, cast in Munich, and installed in Washington, DC in

1871.

In 1856, he completed the statue of President John Adams originally for the cemetery of Mount

Auburn in Boston, Massachusetts.

Following the 1857 death of sculptor Thomas Crawford, Rogers completed the sculpture program of

the Virginia Washington Monument at the State Capitol in Richmond.

He designed four major American Civil War monuments: the Soldiers’ National Monument (1865–

69) at Gettysburg National Cemetery; the Rhode Island Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument (1866–71) in

Providence; the Michigan Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument (1867–72) in Detroit; and the Soldiers’

Monument (1871–74) in Worcester, Massachusetts.

He modelled The Genius of Connecticut (1877–78), a bronze goddess that adorned the dome of the

Connecticut State Capitol in Hartford. It was damaged in a 1938 hurricane, removed, and melted

down for scrap metal during World War II. A plaster cast of the statue is now exhibited within the

building.

In 1873 he became the first American to be elected to Italy’s Accademia di San Luca, and he was

knighted in 1884 by King Umberto I.

Rogers suffered a stroke in 1882, and was never able to work again. He left his papers and plaster

casts of his sculptures to the University of Michigan.